We’d like to thank Jacqui Lipton for this blog post. Jacqui is a Senior Agent at The Tobias Literary Agency and the author of Law and Authors: A Legal Handbook for Writers.

If you plan to write about real people and events, you may face questions about when you need permission to reproduce text, imagery (photographs, maps, charts) or anything else you’ve uncovered in your research. The main body of law relevant here is copyright which basically prohibits reproducing and distributing other people’s work without permission. Note that the law applies to the actual expression of the work—e.g. the actual words the creator has used—and not the idea behind the work. Ideas and facts can’t be copyrighted so you only have to worry about copyright law, and permissions, if you plan to actually copy someone else’s protected expression.

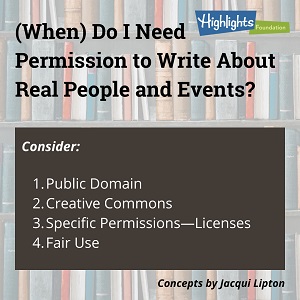

How do you figure out when you need permission to use someone else’s work?

1/ Public domain

The first question is whether the work you want to reproduce is in the public domain. Copyright protection lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years after the author’s death. Many high-profile works fall into the public domain every year. If you’re interested in when particular works have fallen into the public domain, the Duke University Center for the Study of the Public Domain is a useful resource: https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/. Works may be in the public domain either because their copyright term has expired or because they pre-date copyright law: for example, the works of William Shakespeare. Anything in the public domain is free for anyone to use however they like. But do not fall into the trap of assuming that anything accessible to the public (like stuff you find in public libraries or on the internet) is in the public domain. Many things that are free for you to read or watch are still protected by copyright. Just because you don’t pay to read someone’s website doesn’t mean they don’t hold copyright in the website contents.

2/ Creative commons

People often confuse works that are truly in the public domain with works that have been “dedicated to the public domain” under a general license that allows use without payment. Theoretically you can’t really put a copyright work into the public domain until its term expires. What you can do is release the work on the internet under general license terms allowing others to use the work without paying a fee. What is really happening here is a form of permission—a license with terms attached that may be as simple as providing a credit to the original creator, or may include a promise not to make any commercial use of the work. The Creative Commons organization has created a set of general license terms that are used by many software developers and photographers in this context: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/. The main practical difference between the public domain and a creative commons license is that, with the latter, you have to comply with license terms to use the work. For example, if a license only allows noncommercial use of, say, a photograph you want to reproduce in your commercially published book, then you need to negotiate a separate license with the copyright holder allowing your commercial use.

3/ Specific permissions—licenses

If you are working with copyrighted material that is not free for you to use in a commercially published book, your publisher will likely require you to obtain permissions for that material. Your publishing contract will typically make you responsible for obtaining and paying for these permissions although occasionally a publisher will negotiate a permissions budget with you to help defray the costs. To get permission you need to research who holds the copyright and on what terms they are prepared to license it to you, assuming they are prepared to license it. To find out who holds the copyright, you can search the copyright register in the United States. Many copyrighted works also contain copyright notices—with the © symbol—stating who holds copyright and when it was registered. Your publisher should be able to provide a permissions form that you can use when you approach the copyright holder so you have appropriate documentation in place.

4/ Fair use

If the work you want to use is copyrighted and you are unable to obtain permission, you may be able to argue your use is excused as a fair use under the copyright law. Most publishers will require permission rather than relying on fair use because, under the American system, the only way to know for sure whether a particular use is a fair use is to go to court and argue about it which is expensive and time consuming whether or not you have a good case. The American fair use defense requires a court to balance four “fair use factors” relating to: the purpose of the use; the nature of the work that has been copied; the amount of the work copied; and, the effect of the use on the market for, or value of, the original work. These factors are intended to be applied flexibly by courts on a case-by-case basis. This flexibility leads to uncertainty which is why most publishers like to have a permission on file rather than fall back on the fair use defense.

A final caution, and a mistake a lot of people make, is thinking that crediting the original source avoids copyright infringement. Attribution is always a nice thing to do and, as noted above, it can be required as part of a license to use someone else’s work, but it won’t avoid copyright infringement liability.

And, being a lawyer, I must conclude with my usual disclaimer: Nothing in this blog post is intended as formal legal advice and if you do find yourself in a situation where you need advice on a particular issue, seek the assistance of a literary agent, attorney, or legal service.

More about Jacqui’s book Law and Authors: A Legal Handbook for Writers:

Everything a writer needs to know about the law: this accessible, reader-friendly handbook will be an invaluable resource for authors, agents, and editors in navigating the legal landscape of the contemporary publishing industry. Drawing on a wealth of experience in legal scholarship and publishing, Jacqueline D. Lipton provides a useful legal guide for writers whatever their levels of expertise or categories of work (fiction, nonfiction, or academic). Through case studies and hypothetical examples, Law and Authors addresses issues of copyright law, including explanations of fair use and the public domain; trademark and branding concerns for those embarking on a publishing career; laws that impact the ways that authors might use social media and marketing promotions; and privacy and defamation questions that writers may face. Although the book focuses on American law, it highlights key areas where laws in other countries differ from those in the United States. Law and Authors will prepare every writer for the inevitable and the unexpected.