I wanted to share one of the tools from my comedy writing toolbox– a new favorite tool of mine, one that I picked up from Chris Head’s excellent book, Creating Comedy Narratives, where he poses the question: What is the game of your scene?

In his book, Head says, “When you’re trying to work out what your character should do next, don’t ask: what would be funny? Ask instead: what do they do next to try to win? In order to win, your character will…be taking positive action. Their choices and actions should be guided by a desire to get the outcome they want…the comedy coming from having to work with the limited tools at their disposal.”

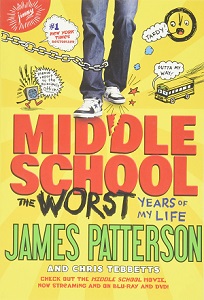

He then breaks the question down into three parts. I’m going to share with you those three parts. For each part, I’ll show how it applies to my co-authored middle grade novel, MIDDLE SCHOOL, THE WORST YEARS OF MY LIFE.

1) What’s the main game of this scene?

What’s the primary action, main idea, or goal for your character here? And what is your strategy in framing it on the page?

For example, the opening scene in MIDDLE SCHOOL, THE WORST YEARS OF MY LIFE shows the protagonist, Rafe Khatchadorian, trying to go as unnoticed as possible through his first day of middle school. That’s not an inherently funny thing, but it is the “game” of my opening scene–trying to go unnoticed.

Now let’s see what happens as we add a few more layers.

2) What’s the sub-game of this scene?

What other idea might you add to bring some further level of engagement for your reader, and perhaps a new obstacle or two for your character?

In the case of my MIDDLE SCHOOL scene, the sub-game is built around Rafe’s active imagination, where he imagines himself entering a maximum security prison instead of instead of Hills Village Middle School. And then–

3) What’s the character game?

What else is going on for your character, often internally, while everything else is unfolding around them? For Rafe, it’s the fact that he just can’t seem to keep his mouth shut. That in turn runs him afoul of the school bully and his homeroom teacher in short order—and in exact opposition to his own intention, to stay as invisible as possible.

Sometimes these three interlocking elements fall into place organically as we write from our own gut instincts about what’s funny and what works for our individual narratives.

Other times, though, I find it useful to consciously consider these ideas, either while I’m conceiving and drafting a scene, or while revising, especially for a moment in the story that feels flat or uneventful to me.

When I come at it with this kind of open-ended, playful thinking, where literally anything goes, the possibilities are endless.

And hopefully, the laughs will be, too.