When did the shag haircut first appear?

How much did a can of beans cost in 1930? What about a crate of champagne?

How many people lived in Atlanta in 1860?

What was the most popular song in December of 1953?

Love it or hate it, there’s no getting around research when you’re writing historical fiction.

Even if your story takes place in an era you’ve lived through, memories are far from perfect and evocative details can slip through the cracks.

As a former librarian, I LOVE research. Tracking down obscure details and poring over primary sources is like a treasure hunt for me. One interesting tidbit leads to the next and soon I’m following a trail of breadcrumbs to a tasty insight I would otherwise never have thought to look for. Alongside the facts you intend to uncover, research can surprise you with details that will enhance your story, invigorate your characters, and maybe even influence your plot.

Want to give it a try and join me on the adventure? Here are 5 places to start.*

1. NEWSPAPERS

Historical newspapers are a terrific resource for getting an overview of daily life in a community in any era. News articles and editorials let you know what was happening and what people were thinking about those events, but there’s so much more: police reports, movie/TV/theater listings, book reviews, community calendars, and advertisements. Read a few months forward and back from the time your story is set and you’ll imbibe a better sense of the language of the day, what things cost, and what was important in that community.

WHERE TO FIND THEM:

Many libraries provide access to ProQuest Historical Newspapers, a searchable online database with full-page digitized scans of newspaper pages, some dating back to the 18th century. Includes US, Canadian, and some International papers as well as American Black and Jewish newspapers. Smaller or more specialized papers may not be digitized and you may end up in a library basement, reading from microfilm or microfiche.

New York Times, January 7, 1917.**

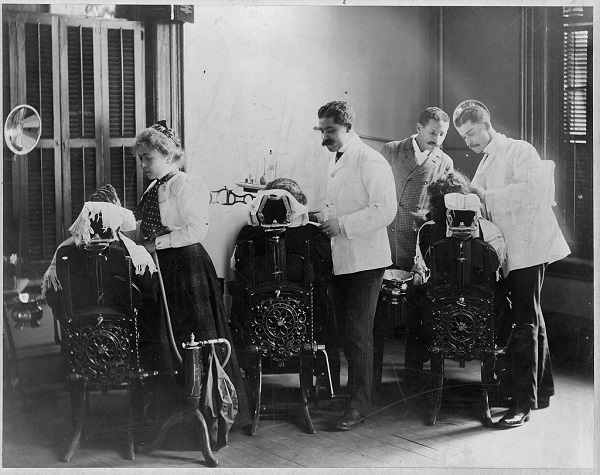

2. PHOTOGRAPHS (mid-1800s on)

As writers we need to use all five senses when conveying an historical world to our readers. But for the author/researcher, there’s nothing quite like seeing a scene from the past. In addition to images that capture major historic events, more casual photos reveal landscape and architectural details, fashion, past-times, and all those wonderful human faces and candid expressions— that just might get you thinking about your own characters.

WHERE TO FIND THEM:

- Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online http://www.loc.gov/pictures/

- U.S. National Archives Digital Photography Collections https://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/photography

- Significant events in US History, the American West, Black soldiers in WW2, Japanese internment during WW2, Pearl Harbor, 1963 March on Washington

- GETTY: A fee is required to license or reproduce but viewing is free. Search their editorial collection of millions of news, sports, entertainment & archival photos by region, keyword, date and more https://www.gettyimages.com/

Students learning dentistry at Howard University, circa 1900.

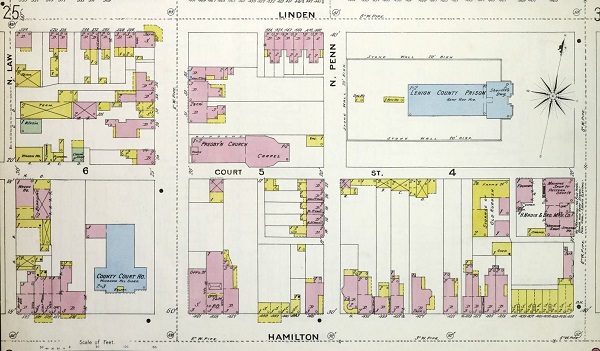

3. MAPS

Especially in urban settings, maps give a sense of the topography and scale of the historical location. How far was it from your character’s home to their school, the park, the riverfront, the bus station? What neighborhoods were nearby? Comparing maps of different dates for the same place can show how quickly a city is growing. Is your story’s locale a lazy place where nothing ever changes? Or a boom town with new streets stretching into the countryside every day?

WHERE TO FIND THEM:

- Sanborn Maps were made for fire companies to assess liabilities in urban areas in the 19th and 20th century and give a detailed view of neighborhoods. https://www.loc.gov/collections/sanborn-maps

- Bird’s eye view maps. Hand-drawn maps that portray a city as if seen from above. Popular from the 1860s -1920s. Though not drawn to scale, they show the street grid, individual buildings, and major landmarks https://www.loc.gov/collections/panoramic-maps/?fa=subject:aerial+views&sp=3

- Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas, Austin is a good place to start for other kinds of historical maps of the world https://maps.lib.utexas.edu/maps/map_sites/hist_sites.html

Detail, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Allentown, PA 1897.

4. ORAL HISTORIES

Some of your best ‘finds’ may come from these recorded interviews, with usually ordinary people who have lived through historical events, talking about their personal experience. These are wonderful for understanding historical context and developing well-rounded characters. Though subjects interviewed are usually adults, they often reflect on their childhood. Oral histories introduce personal anecdotes and can tell you how people felt about historical events, plus attitudes towards health, family, religion, ‘progress’ and other issues.

WHERE TO FIND THEM:

Unless you are researching a major historical event, local/regional libraries, historical societies, and archives will be your best bet. Sometimes a simple Google search for your time/region/event + “oral history” can point you in the right direction.

“Hardly was a cabin built in the most out-of-the-way part of the mountains, before a large family of rats made themselves at home in it….They are very destructive, and are such notorious thieves, carrying off letters, newspapers, handkerchiefs, and things of that sort, with which to make their nests, that I soon acquired a habit, which is common enough in the mines, of always ramming my stockings tightly into the toes of my boots, putting my neckerchief into my pocket, and otherwise securing all such matters before turning in at night.”—Excerpt from Three Years in California (1851-54) by J.D. Borthwick.

5. PEOPLE

When all else fails—talk to someone! Universities are full of experts on almost every topic under the sun and many are open to discussing their work with an interested and informed member of the public. And don’t overlook ordinary people. Chances are someone in your network has expertise that could be valuable for your research – from technical or professional knowledge to personal experience. Crowdsourcing from online message boards or interest groups can also yield unexpected gems.

IF ALL ELSE FAILS, ASK A LIBRARIAN!

* Listed resources focus on US history. Other countries will have similar resources to varying degrees.

**All images courtesy Library of Congress.