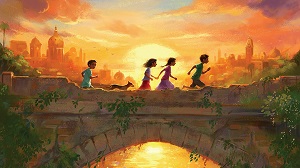

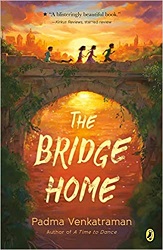

Dr. Padma Venkatraman is the author of THE BRIDGE HOME which has garnered 8 stars and has been honored as one of the best books of 2019 by Kirkus, NYPL, Chicago Library and others. THE BRIDGE HOME is also the recipient of a Walter Award, through the We Need Diverse Books organization, a Golden Kite Award from SCBWI a South Asia Book Award, a Nerdy Book Award, a Crystal Kite Award and a Paterson Prize. THE BRIDGE HOME was the global read aloud book for 2019.

Dr. Padma Venkatraman is the author of THE BRIDGE HOME which has garnered 8 stars and has been honored as one of the best books of 2019 by Kirkus, NYPL, Chicago Library and others. THE BRIDGE HOME is also the recipient of a Walter Award, through the We Need Diverse Books organization, a Golden Kite Award from SCBWI a South Asia Book Award, a Nerdy Book Award, a Crystal Kite Award and a Paterson Prize. THE BRIDGE HOME was the global read aloud book for 2019.

Padma is also the author of A TIME TO DANCE, ISLAND’S END and CLIMBING THE STAIRS. She has spoken at Harvard and other universities; provided commencement speeches at schools; participated on panels at venues such as the PEN World Voices Festival; and been the keynote speaker at national and international conferences and literary festivals. Her next novel, BORN BEHIND BARS, will be released on September 7, 2021 from Nancy Paulsen Books, Penguin Random House.

Visit Padma at www.padmavenkatraman.com or follow her on Twitter @padmatv or Instagram @venkatraman.padma.

We are grateful to Padma Venkatraman for this blog post, derived from a talk she gave during our online course Craft, Community & Your Career.

“…a book as half a bridge, and half a bridge only…”

The pandemic has changed me in many ways. Before the COVID-19 pandemic began, I often spoke of the power that words have to break walls, and I referred to books as bridges. I continue to think of these ideas as valid, but the past year has made me also consider the deeper validity of another metaphor that emerged in my mind. That of a book as half a bridge, and half a bridge only.

More and more, I see that a story-teller shapes only part of tale–the story itself is completed by the reader. I always thought of myself, in the role of author, as one engaged in a co-operative endeavor, which requires two for completion. I always knew I was not THE creator, but A creator because a book is co-created and reborn each time a reader (or listener) experiences it.

When I center this thought, it liberates me from feeling possessive of my work, while also deepening my sense of the importance and necessity to do my best to be sensitive and sensible as I move through my writing life, to the best of my ability. Because my story will be felt by other souls and other minds in ways that my own can never fully grasp, I need to do all I can to ensure my words inspire positive change in a child. This doesn’t mean shielding a child, it means being responsibly honest, and editing my work to ensure it’s age appropriate (although this is a constantly changing more).

“I need to do all I can to ensure my words inspire positive change in a child.”

When I see myself as the builder of half a bridge, when I see a book as one half of an Anjali Mudra, a half-lotus gesture open, offered to the world, waiting for the reader to complete it, I am both humbled and acutely aware of the hard task I’ve set myself. For half a bridge to stand and invite others, it must be built as best it possibly can. For half a bridge to meet a child reader, I must strive to situate it in a place where a child can safely wander.

When I see myself as the builder of half a bridge, when I see a book as one half of an Anjali Mudra, a half-lotus gesture open, offered to the world, waiting for the reader to complete it, I am both humbled and acutely aware of the hard task I’ve set myself. For half a bridge to stand and invite others, it must be built as best it possibly can. For half a bridge to meet a child reader, I must strive to situate it in a place where a child can safely wander.

To me, this means centering both the children within me and the children without me. It’s about not getting overly attached to how the book “does” in terms of sales or other material measures of success. Instead, it’s about understanding that a book is a dance between the material object we create and the energy that’s sparked when a child enters it. Because, although I don’t want to mix metaphors, books also serve as doors through which children walk – not merely to another place or time but into, potentially, another mind, heart and body.

“Introspection and self-reflection help me explore issues of privilege and bias that may lurk inside me, so that when I interact with children, during school visits, I can remain attentive to them and provide respectful responses to all and each.”

Centering the child means respecting and understanding and dedicating what time I can (while giving myself the self-care I need) to diversity, equity and inclusion in our field. Because when we put children at the center, when we move aside to make space for them, we must ensure the space we create is one that nurtures all and each of those children. Introspection and self-reflection help me explore issues of privilege and bias that may lurk inside me, so that when I interact with children, during school visits, I can remain attentive to them and provide respectful responses to all and each.

It also means considering whether I’m the right person to tell a story–in the context of the child who may someday see me in a classroom. For example, if you’re a white author and your research indicates that most nonfiction books about African Americans or Civil Rights are written by white authors and these authors are the ones being invited again and again year after year, to speak to children, you might wonder if it is your place to write another nonfiction book featuring an African American historical figure.

I can’t give you an answer, but I can suggest you think about the child before you arrive at your answer. Deeply and as unselfishly as possible. Sometimes, it’s not only a question of giving what we can when we can for the cause of diversity, but also giving up something if we can. This is not to say we must sacrifice ourselves. Absolutely not. It’s vital that we protect our work and assert our individual rights and unique voices–but maybe we don’t have to pursue every story that pops into our heads.

“Centering a child means nurturing our community of creators and educators and communicators committed to children’s literature–learning and unlearning as needed.”

Centering a child means nurturing our community of creators and educators and communicators committed to children’s literature–learning and unlearning as needed. In terms of unlearning, it’s sometimes as simple an issue as language. In my case, I have striven to break the habit of referring to audiences as “you guys” – maybe it’s unimportant to some, but it felt important to me (especially as I was often the only BIPOC female or only female for many years when I was a scientist). Change is hard, but it becomes easier when we center the child and the child’s future.

For example, what happens when we convey to children a conviction that, for instance, Copernicus was the first ever human to even think of heliocentricism, and speak of “THE Copernican revolution” or THE ENLIGHTENMENT? Doesn’t it imply that white males matter more than others and also (falsely, I might add), assume that no one else contributed anything of value to science or mathematics or modern art or music etc.?

For example, what happens when we convey to children a conviction that, for instance, Copernicus was the first ever human to even think of heliocentricism, and speak of “THE Copernican revolution” or THE ENLIGHTENMENT? Doesn’t it imply that white males matter more than others and also (falsely, I might add), assume that no one else contributed anything of value to science or mathematics or modern art or music etc.?

If we value every child, we might seek to be sensitive to us and them, to the other-ing and potential superiority inherent with which phrases such as WESTERN VALUES may be imbued in certain sentences and contexts–west of what? And who do we exclude and how dare we, when we elevate our beloved nation above all others? Can we not passionately love our country without saying it is THE best in every way? I, for one, think it’s usually a better choice to use “a” in place of “the” – and to qualify that a certain value is one I hold dear, but it is a human value, that has also been held dear by other cultures, and so on.

If we center the child for whom we are buying/teaching/reading a book, isn’t it the child and that child’s needs and interests that matter more that one’s own childhood memories of loving an old “classic”, that may contain potential damaging or painful words or concepts that can seep in insidiously? And if there are good arguments to present such books to children, centering the child might energize us to at least discuss and scaffold and contextualize and present alternatives and pairings that are true pairings, in which both books are given equal weight.

Centering children also means behaving more mindfully, especially in public spaces. I don’t engage in call out culture because I’m uncomfortable with it, although I understand and fully respect others who feel this is a very important aspect of speaking up for diversity. So I do address issues directly, one on one. And I think, regardless of one’s chosen mode of action, it may be worth remembering that what we say and do on social media, leaves footprints that may be tracked by a child someday. In my case, I try to remain true to myself, while remembering I may be seen as a role model by a child.

“…I dislike hierarchies and would prefer for children to grow up in a world in which many existing hierarchies are dismantled…”

Because I dislike hierarchies and would prefer for children to grow up in a world in which many existing hierarchies are dismantled, I also frequently engage in self-reflection. In a field that is female dominated, how is it that men are so often elevated and celebrated? Can we prevent ourselves from, for example, finding male ambition cute when it is overtly expressed while demeaning a woman who dares express her dreams?

When we speak of books we love, can we celebrate not only authors who’ve won the highest awards, but also those whom we think deserve them but might not have such recognition as yet? These actions break down hierarchies, lift relatively unheard diverse voices, and send a message to a child that gifts and rewards may not always be tangible or visible or otherwise evident.

Centering children also inspires us to seek truth. Even if truth flies in the face of what our family or community may believe. It gives us the courage to speak up. It encourages us to be truthful, to set a good example, by, for instance, pledging never to plagiarize/steal words/ideas. To respect verbal copyright. If we want the spotlight to shine on us, we may be tempted to take another person’s words without giving due credit. But if we center the child, then ethical behavior takes precedence. As does education and looking back and paying attention to giving due credit to those who came before us.

In science we always cite and reference prior contributions. In the field of children’s literature we don’t always acknowledge previous achievements. The more silver I see in my hair, the better I understand ageism. The young are cool and have much to offer, and we have wisdom and are just as cool. And that’s an important message in a child-centered world.

In science we always cite and reference prior contributions. In the field of children’s literature we don’t always acknowledge previous achievements. The more silver I see in my hair, the better I understand ageism. The young are cool and have much to offer, and we have wisdom and are just as cool. And that’s an important message in a child-centered world.

“We must invite our co-creators to finish our bridges in whatever fashion they see fit. We must remain on our side, compassionate, mindful, attentive. The rest is up to our co-creators.”

I feel compelled to clarify that seeking truth also means respecting a child’s right and freedom to choose what to think. It’s not our place to hand them dogma. Instead, allow words to inspire questions within a child, complex questions to which there may be several different and equally valid answers. Let’s give the children who complete our bridges the trust and the confidence to ponder and decide their own answers. We must each decide what we feel is alright for a particular age group and so on, but we cannot preach. We must invite our co-creators to finish our bridges in whatever fashion they see fit. We must remain on our side, compassionate, mindful, attentive. The rest is up to our co-creators.