Traci Sorell

Karen Boss

Special thanks to Traci Sorell and Karen Boss for this blog post.

Traci writes fiction and nonfiction books as well as poems for children and Karen is her editor, with Charlesbridge.

Any healthy relationship involves communication, collaboration, and mutual respect. It’s no different in the publishing world between a creator and editor. Feeling comfortable about expressing concerns of any nature–about a manuscript, about edits or provided feedback, or about how the publishing process works–requires a level of comfort and trust.

For those from underrepresented communities, such as citizens from Native Nations, the power imbalance between the publisher/editor and the creator (author/illustrator) can often weigh heavy on the relationship. The editor at the publishing house seemingly has all the power, right? Yet, the author or author-illustrator is the one who started the relationship by writing a story and bringing it to the publisher in order to share it with the world. So reframing the relationship to acknowledge how both can be empowered is critical.

Working Together for Correct Information

Currently, there are no known citizens of Native Nations working full time as children’s book editors at publishing houses in the United States. Much like the rest of the general populace, most editors, regardless of their own background, usually lack any meaningful knowledge about the history (political or legal) and culture of the more than 570 Native tribes in the United States. So the creator can definitely serve as an educator for the editor and the rest of the publisher’s staff. The creator has the ability to share their knowledge, not only about the content in their book, but also what can’t or shouldn’t be added because of cultural mores or inaccuracies to the experience of the characters. It can be stressful to operate in this role, since no one person holds all the cultural and linguistic knowledge about any Native Nation. That’s why it’s important for publishers to be supportive of others from the Native Nation to serve as content advisers to ensure all representation (linguistic, cultural, historical, etc.) is correct. It allows a published work, whether fiction or nonfiction, to be one that readers can rely on for correct information.

And it’s equally important that publishers and editors not ask Native creators for all the answers. Editors doing their own homework and reading and research is important. Editors have the ability to ensure that information about the book flows correctly from editorial to other departments in the house. Sharing what editors come to know with sales and marketing staffs helps to take the burden off the creator to do all the teaching.

Our Own Working Relationship

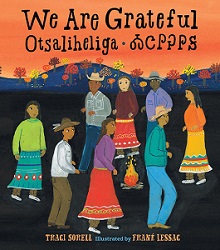

We’re grateful that we’ve established this type of working relationship during the process of bringing We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga to the market. Traci was, from the start, looking for the book to be three things: a place where Cherokee kids could find themselves in the pages of a book, a place where other Native and non-Native kids could learn about contemporary Cherokee people, and a book with commercial success. And Karen had those same goals. Karen is grateful that Traci was never shy, and always willing to speak up about how or why something should be explained or rendered in a certain way in the book. And Traci hoped to work with an editor who cared about getting it right. She found in Karen someone who is willing to figure out (and hear from others) what she doesn’t know. What we don’t even know we don’t know is often one of the biggest problems in both writing and editing, we think. And we agree on another thing, too: Unless the project is work for hire, the creator should feel really good about what goes out under their name.