As someone who writes a lot of middle grade material that is meant to be fast-reading and narratively compact, I spend a lot of time thinking about the economy of my writing, and what goes into it.

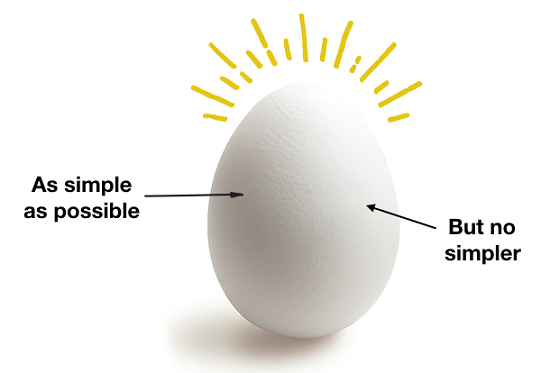

One of my guiding principles echoes the famous Einstein quote, that “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” For me, that means keeping my prose as clean and focused as I can, while also making sure that I don’t overdo it with the economy. I don’t want to be stingy with my storytelling. Rather, I want my stories to be dense and flavorful, and I want everything I include to be there for a reason. To that end, here are three things I watch out for:

1) REDUNDANCIES. This can be deceptively tricky. Some repetitions and unnecessary passages are obvious when I read through a draft, but others can take a while to uncover. Consider this line and see if you can spot the redundancy:

“Burton was asleep on the bed, his closed eyes twitching lightly and his arms wrapped around a pillow.”

Do I need to mention the closed eyes of a sleeping character? I would say probably not. And then, how about a line like this:

“What happened next changed everything.”

That might be a perfectly good setup, depending on the context. On the other hand, am I just telling my readers something that I’m about to show them, anyway?

Those are just two smallish examples, but I find that the more deeply I read in the revision phase, the more redundancy I tend to find.

2) TOO MUCH OFF-CAMERA TIME. For the style I write in (and, I would say, for middle grade in general), it’s important to keep the story moving along, and to keep things happening on-camera, so to speak.

Off-camera moments, as I think of them, include anything outside the events of the scene itself: description, internal monologue, narration, flashback, reflection. These are all important ingredients, but I try to keep my proportions weighted heavily toward the on-camera side of things. My own rule of thumb is that I only allow myself one or two off-camera passages per scene or chapter. That doesn’t include descriptive phrases or momentary asides, but it does include any multi-sentence diversion from what’s happening in the here and now of the story.

3) STARTING A SCENE OR STORY AT THE RIGHT MOMENT (AKA, AS LATE AS POSSIBLE). One of the most common mistakes I see in student manuscripts is over-long beginnings. It’s not uncommon for me to point out to another writer that her drafted story doesn’t actually begin until page three, or chapter two, or whatnot. This is often the result of the author working through her own discovery process, which can mean putting down a lot of ultimately expendable exposition as she drafts through. When I write, I try to bear in mind the slippery difference between what I need to know in order to tell the story, and what my readers need to know in order to enjoy it.

It’s the same thing with scenes. Do you ever notice on t.v. how often characters skip the “hello…how are you” and “goodbye…see you later” parts of their conversations? When you notice, it can seem unrealistic, but overall, the story moves more gracefully along when the storyteller lets go of those ultimately static moments. Take a look at a few scenes you’ve written and ask yourself: where does this scene really begin? And, while you’re at it, where does it really end?

As a caveat, let me add that none of this is about hard and fast rules. Context, style, and the individual needs of a given story all need to be taken into account. But I do find that deeply combing my manuscript for expendable material can really pay off. Bit by bit, it may not seem like much, but in the aggregate, it can add up to a significantly smoother, more engaging reading experience for your audience—and a better book for you.

Happy reading, and happy writing!

Chris Tebbetts

Find me online at www.christebbetts.com and @christebbet