Here are my three tips for writing funny picture books:

Here are my three tips for writing funny picture books:

Tip #1: Give your characters ridiculous names.

You may not end up keeping them. Or, your readers may not ever hear them (since unnamed characters show up much more often in picture books than in other types of fiction). Still, they will inform the spirit of what you write. Boompus! Fiddlestick. Furball. Hairball. Jones-Merriweather-Fotheringill. Whatever makes you laugh.

Try switching them out for new ridiculous names and see what that does to your manuscript!

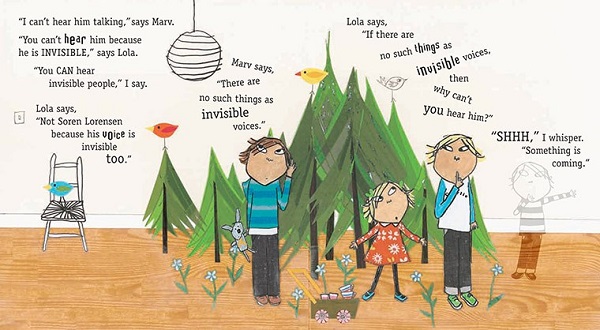

The example below, from Lauren Child’s I am Absolutely Too Small for School, shows you her heroine Lola’s imaginary friend, Soren Lorenson, and her brother’s neighbor friend, Marv. And Kwame Alexander makes the funny name the centerpiece of Acoustic Rooster.

Tip #2: Put some outrageously long words in there, just to see what they do.

Picture books don’t have to have limited vocabulary. In fact, one of their jobs is to to expose children to new vocabulary.

Here are some useful ones to try that seem to me to fit the emotional lives of children: consummate; incorrigible; flabbergasted; celebratory; schaden-freude. But feel free to use any delightful verbiage that’s organic to your subject. You may choose to cut it out in favor of simpler wording, later – but you also may find your text has some increased complexity and depth because of the specific word choices, or a new kind of rhythm.

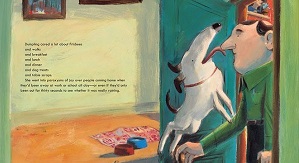

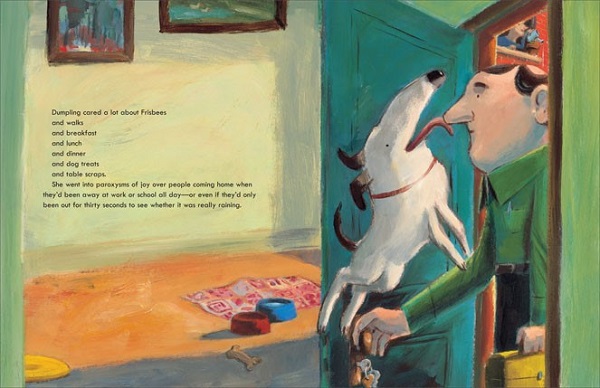

Here’s an example from an older book of mine, Skunkdog, which uses the word paroxysms, And from Daniel Bernstrom’s delightful One Day in the Eucalyptus, Eucalyptus Tree, where the big word actually becomes a guiding rhythm of the book.

Tip #3

Hit return a lot.

Like,

in the middle of sentences.

It’s fun!

And

it helps you

control

your read-aloud.

As with the other stuff, you can always go back to more standard prose, but I think you’ll find that you see rhythms and repeated structures–things that are probably already in your text!–better when you play with that return key.

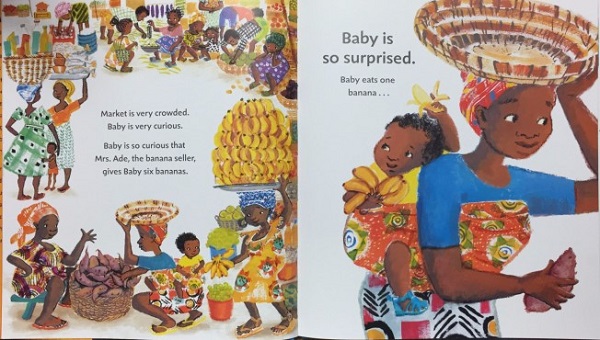

Those are elements you can now play up to create a compelling read-aloud, and the line breaks serve as a guide to the people who will read your stories aloud to young listeners. Here’s an example from Atinuke’s Baby Goes to Market. The line breaks throughout the text highlight the names of each person Baby encounters, and then highlights the gift Baby receives. The page break and the ellipse on the right-hand page force us to read aloud with expression, and putting “Baby is” on a line of its own pushes an adult reading aloud to put a little pause there. The larger type likewise encourages emphasis in the read-aloud.