Since I taught at the workshop Getting Your Middle Grade and Young Adult Novel Unstuck, I’ve been thinking about ways to get characters “unstuck.” Recently in The New York Times, I was struck by a quote from the writer Lawrence Osborne (author of Beautiful Animals.) He said, “I’ve got everything against likable characters. Likable characters are usually completely forgettable and we don’t really care.”

The qualities that make someone likable can seem ordinary and boring in a book character.

That statement certainly flies in the face of conventional wisdom. Think how often as a writer you’re encouraged to create likable characters. In the holy grail of what makes a book memorable and successful, we’re often told that a likable character is essential. But I think Osborne has a point. The qualities that make someone likable–friendliness, kindness, reliability–can seem ordinary and even boring in a book character. In thinking about my favorite children’s book characters, I wonder if what they have in common is less “likability” than something more elusive, something I’ll call charisma.

Peter Pan. Pippi Longstocking. The Pigeon. Junie B. Jones. We certainly don’t remember them for their virtues. Peter Pan is headstrong and selfish; Pippi Longstocking is impulsive and impractical; the Pigeon is hopelessly stubborn; and Junie B. Jones wants what she wants with no regard for anyone else.

And yet, they win our hearts. They may not be “likable” in the traditional sense of being nice or easy-going, but each has oodles of personality and a compelling aura that mesmerizes readers. We know they’ll stir things up. We can’t wait to see what they’ll do next.

If charisma is the key to a memorable character, the question for writers is, how do we create that on the page? First, let me say: there are no rules. What follows–which, I admit, looks like a bunch of rules–is only meant as a jumping-off point, not any kind of formula. Your own mileage will vary, but here are a few things that can be helpful in creating characters that are memorable; characters with charisma.

1. Make your character funny.

Humor can compensate for a whole host of off-putting personality traits. As a reader, have you ever met a funny character that you didn’t like? This tactic won’t work for every story, of course, and not every main character can or should be funny, but if your character has the ability to make the reader laugh, a lasting bond develops. Think of Mo Willems’ Pigeon resisting bedtime with a bullhorn, yelling, “Hey, hey! Ho, ho! This here Pigeon just won’t go!” He’s irresistible.

2. Give your character a defining quirk or two; an obsession; a mania.

As readers, we’re drawn to weirdness. It makes a book and a character riveting, especially since we don’t have to live with it ourselves. Pippi Longstocking lifting her horse over her head? Weird, and unforgettable.

3. Make your character desperate.

A certain level of distress or last-ditch desperation can lend not just suspense to a book but a great opportunity for the reader to root for your character. Think of Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz; what propels her and indeed the entire story is her desperation to go home. Writing classes often advise you to ask, “What does my character want?” But in thinking about desperation, we can go further. Ask, what does your character need? What’s her darkest secret? What does he fear most? What’s the one thing he just has to have?

4. Show your character’s flaws and blind spots.

Characters who are flawed are accessibly human. Their jealousies, insecurities, worries, and self-doubts are ways for the reader to know them better, to understand their most fundamental drives. Likewise, their irrational loyalties and unjustified affections help the reader feel tenderness toward them. In E.L. Konigsburg’s Silent to the Bone, Branwell keeps a devastating secret to protect a babysitter he has a crush on. Children’s book writers are often told to have their characters “solve their own problems,” without the aid of the adults in the story, but it can be equally valuable to have characters create their own problems; and a blind spot can be an excellent cause of problems.

5. Have your character break the rules.

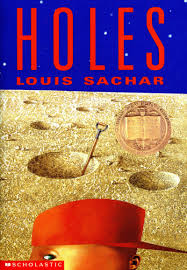

Not every character has the personality to do this in a credible way, but even if he or she does it accidentally, it creates a situation where the reader will become invested in the consequences. And again, it’s a terrific way to inject suspense. Think of Stanley Yelnats in Holes, stealing shoes and then a truck to go after Zero. For the reader, rule-breaking is both worrisome and thrilling.

6. Give your character a moral dilemma.

Moral quandaries offer rich terrain for revealing character, and they tend to make a reader sympathetic with your character’s plight and anxious about outcomes. In Frances O’Roark Dowell’s Dovey Coe, the title character is faced with the moral dilemma of telling the truth or protecting her deaf brother from harm. It’s wrenching.

7. Make your character vulnerable.

You will notice that many of the preceding suggestions have this effect. I remember reading once that if you want readers to bond with your main character, put him in love or in trouble on the first page. Readers are instinctively drawn to and protective of characters who have a lot at stake. A difficult situation with a high emotional impact on the character will sow the seeds of compassion and affection in the reader. Think Wilbur. Or Ramona Quimby. Or Harry Potter. These three characters could hardly be more different from each other in personality, from Wilbur’s sweet yearnings to Ramona’s brashness to Harry’s stoic determination, yet they’ve attracted legions of devoted readers. What they have in common is that they’re all in big trouble. Wilbur is facing the butcher’s knife; Ramona is endlessly courting mischief; and Harry is the moving target–across seven books and thousands of pages–of the Dark Lord’s murderous wrath. As writers, if we want the reader to be on our character’s side, we need to create the hurdles, enemies, and dangers that will put them there.

One final note:

Don’t neglect sidekick characters when you think about charisma. Remember, none of your secondary characters are secondary characters in their own lives–they’re the stars of the show! As such, they are equally deserving of a sprinkle of charisma, to engage readers in their circumstances.

The fashion designer Coco Chanel once said, “You can always have charm. It’s better than beauty. It lasts longer.” This seems especially true of children’s book characters. The ones with charm, or charisma, may not be “likable” in a traditional sense, but they capture our hearts as young readers—and if we’re lucky, they stay with us long into adulthood. A healthy dose of charisma, through tactics like the ones described above, can be a great way to get your character unstuck. Happy writing!