A few weeks back, we hosted 19 folks at our Whole Novel Historical Fiction workshop. Mealtimes were lively with this group as they volleyed historical facts across the table.

First, a trip to 1940s Wyoming with conferee Mary Louise Sanchez’s Cutting the Strings: “On the wall, Beth’s family had a world map marked with a path of tacks lined up like soldiers stretching from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea and across southern Italy…The tacks, which looked like eyelets on the Italian boot, showed the route where Beth’s family thought her brother, George, had taken to where he was fighting now.”

Then to the 1800s with Kim Silva’s A Sign of Freedom: “Her mother, Nellie Davenport, and her deaf family members shook their heads in dismay over the changes at the first school for the deaf. All the schools for the deaf had now adopted the oral method and forbade Sign Language. The American School for the Deaf still hired deaf staff in the dormitory, and protests from the school’s alumni had forced the administration to retain two respected deaf teachers at the school. Sign Language and pride in the school’s history continued to flourish in secret, despite the official philosophy that all deaf students should, and could, learn to speak.”

Historical events crossed from one side of the table to the other as the group shared stories and research. In a group like this, historical fiction is not a forgotten genre but the heartbeat of what engages readers in our shared humanity. Faculty member Ashley Hope Pérez stated, “Historical fiction can help us amend our imagining of the past to include the experiences of minoritized people, which have too often been relegated to the margins of mainstream histories or erased altogether. We all need to engage with these stories.”

Historical Realities in Fiction was a four-day retreat for writers to build a deeper understanding of the role fiction plays in understanding our shared history. There were daily lectures from the faculty, paired with one-on-one mentoring and deep discussions on the responsibilities of writers to “get it right.”

Donna Jo Napoli and Marilisa Jiménez García generously shared details about the workshop with us:

Alison: Welcome, Donna Jo and Marilisa. We are honored to host you in the blog today. Let’s start with a bit about your current writing projects, and then move into details about the workshop that you’ve crafted for the Foundation.

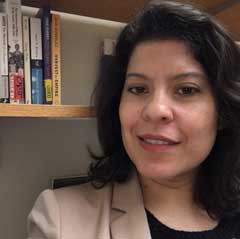

Marilisa Jiménez García

Marilisa: Hi, Alison and all! My writing is about weaving together histories and texts that often get left out of the big picture in Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. literature. I feature a lot of woman and men of color who wrote for young people. These kind of stories are often seen as just didactic and having a moral – people don’t often focus on the nuances of literature for young people as itself an art form and a powerful tool for thinking about ethnic studies, U.S. history, and the history of oppressed peoples.

I try to “tell a story” with my scholarship by including different views and centering those who are not often heard. Right now, I am working on a book about Puerto Rican/Latino children’s and young adult literature. Along with my other studies, I am excited to take a trip to Puerto Rico to do some research and hang with family.

Donna Jo: I’m just finishing up Hunger, which is a middle grade novel that opens in autumn 1846 in the west of Ireland.

Donna Jo Napoli

I’m also in the middle of a book of Bible tales, from Genesis through Kings. This is part of a series I’m doing with National Geographic. I had very little understanding of the ancient Bible before I started – I just saw it as a fascinating narrative. But in writing this book, I met with a rabbi at least once a week, and often multiple times, from September 2016 through the end of February 2017. She took me through the Hebrew text and discussed a whole range of things with me that I’d have never been able to glean from English translations. That made me recognize threads tying together many stories – and I’m hoping that will help make the final book cohesive.

There’s still editing to do. And since this series is heavily illustrated, there will be edits to do to make the text sit nicely on the page once the illustrations are in place – things like “add 120 words” or “cut 43 words.” I know for writers this sounds horrible. How can you adjust your text – your ART – to formatting restrictions? Well, the way I do it is to climb off my high horse (or not climb on in the first place) and recognize that the art pulls in some readers while the text pulls in others, and the concert of the two pulls in yet others. I absolutely adore the work of the illustrator for the series, and I trust NG to know how to reach the widest audience. That’s what I want, after all – to reach readers.

Alison: While many of your projects have historical undertones, today’s political climate and human interests undoubtedly influence them. How can historical fiction help our children gain an understanding of the past, as well as the impacts these events have on their future?

Donna Jo: I’m glad you asked that, because it is concerns in today’s world that made me interested in writing Hunger. As the story opens, the potato famine has been going on for a whole year already. We follow the children in a set of families through what it means to be hungry, to be surrounded by death, to live with adults who have little to no hope, to recognize the unfairness of a situation that has a dramatic contrast between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” Through connecting to these children, I hope the reader will come to understand both how hard it is to leave your country and how hard it is to stay behind to try to rebuild it after a catastrophe.

Many children in America are of Irish descent. And many others have either positive feelings toward those of Irish descent or, at the least, little prejudice against them. Reading about the ancestors of Irish Americans may allow children to empathize with them in what was a terrible situation. This empathy might generalize and help children to appreciate the value immigrants bring to whatever new society they join. In today’s world, one of the biggest social issues is how to deal with people who must leave their homelands. How should we treat them? What is right and decent? What is best for ourselves and for the world?

Marilisa: I think widely about this when I teach. What books are out there to raise the narrative? There are some great examples. I just finished teaching Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez, which shows a multitude of perspectives, which my students loved (and needed to see in print). It also really denies readers of a so-called “happy ending,” which is important in a narrative like this one. I also taught Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older, which students really appreciated for how it portrays the dynamics between those “who study and those who get studied.”

Further, I wrote a dissertation on Puerto Rican children’s literature and how so many authors have used children’s and young adult literature to document the intricate histories of Latinx communities, including consequences of colonialism. My background is in Latinx studies and specifically Puerto Rican studies, particularly thinking about the Puerto Rican diaspora. For example, you also see how authors present young people with tools for how to resist and rewrite the oppressive circumstances around them and teach them how to write a new story.

Alison: Bringing these thoughts to your workshop, what can writers expect from attending Historical Realities in Fiction?

Marilisa: I hope writers can think about how they might create more nuanced perspectives of historical accounts, particularly those portraying people of color. Often, even in our Latinx literature, we privilege perspectives of characters with lighter skin and those who have access to certain kinds of power and wealth. How can we tell stories that show more than one side of the story while portraying characters as having agency, creativity, and dignity? It is possible, but it takes work.

Donna Jo: I encourage writers to deal with issues they care about deeply in ways that resonate with their own needs and goals as writers. If they do that, my hope is that they’ll come up with something unique – something only they could have written in precisely that way. I follow my own advice on this. For example, I chose a setting in which hunger is a motivation for emigration because hunger matters to me profoundly. I grew up dirt poor, and in high school I went to bed hungry more often than not. I could have, instead, chosen a setting in which war is a motivation for emigration (as it is in various parts of the world today), but I didn’t because, while war also matters to me, my own experiences with hunger are more visceral than my experiences with war – so I had more to go on – and that more was from a child’s perspective.

A historical setting gives one a world to move around in – so many details, all fitting together perfectly. But how you move in that world can vary enormously. I love both realistic and fantasy fiction. While today so much fantasy fiction is set in the future, there are unlimited opportunities to set it in the past. There are opportunities to ask “What if?” How would history have changed if only something critical in that world had not been there or had been different? Or, simply, how can I make readers trust my fantasy by drawing on real-world facts? That’s a question I’ve asked repeatedly in doing fairy tales.

So those who attend do not have to be wed to any particular genre or any particular perspective. They just need to be ready to dig inside for something they honestly and, indeed, desperately, care about – and then get to work with us on making headway.

Alison: Thank you, Donna Jo and Marilisa!

— Interview by Alison Green Myers