In a fervent effort to procrastinate from writing a synopsis, I found myself organizing notebooks. I know that a veterinarian reading this post might not understand the delight in this activity, but you, my fellow book creator, do. Not only had I found a way to escape the clutches of writing and rewriting (and rewriting) a synopsis, I found mountains of notebooks filled with notes from old critique group meetings and workshops.

What a find! One was covered in hurried writing, the way a notebook looks when you are desperate to capture everything a speaker says. The speaker in this notebook’s case was Patti Gauch. The topic: VOICE.

“Attitude should drive the story, the chapters. Voice has opinions, thoughts.”–Patti Gauch

Voice has opinions. I could distract myself for days on that statement alone. It does have opinions, doesn’t it? Why, with being so bossy or sassy or unreliable, that Voice does want to tell things a certain way, in a specific order, with all of her moxie in place.

Maybe that is why we love Voice as much as we do? Maybe that is why we seek it out when reading through a pile of manuscripts or selecting a new novel from our TBR pile?

“I sit down with the manuscript, look at the first page. If I ‘hear’ Voice in the language of the storyteller on that first page, I will read on. If I read flat storytelling without passion or individuality – without Voice – I will simply fold the title page over, put the manuscript back in the brown envelope, and send it back to the writer.”–Patti Gauch

I love that in all of Voice’s determination, when it comes to a novel, she only reveals herself to the ear. We hear Voice. She may dress herself up as a character and stomp through the pages of the novel itself, but her words will be the only anchor to give us a sense of who she is and what she stands for. In any situation, we know how Voice would react. In any setting, any relationship, Voice is unique in her verbiage, in her pacing and tone, in her humor and anxiety. Voice has opinions. And she’ll make them known.

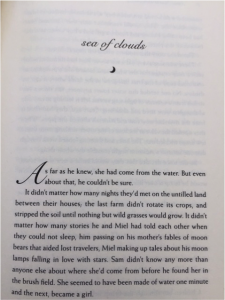

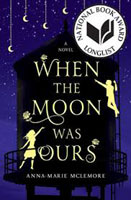

Look at Voice in Anna-Marie McLemore’s When the Moon was Ours.

As far as he knew, she had come from the water. But even about that, he couldn’t be sure.

It didn’t matter how many nights they’d met on the untilled land between their houses; the last farm didn’t rotate its crops, and stripped the soil until nothing but wild grasses would grow. It didn’t matter how many stories he and Miel had told each other when they could not sleep, him passing on mother’s fables of moon bears that aided lost travelers, Miel making up tales about his moon lamps falling in love with the stars. Sam didn’t know any more than anyone else about where she’d come from before he found her in the brush field. She seemed to have been made of water one minute and the next, became a girl.

I hear Voice in this opening like crashing waves, like the ebb and flow of water. It is reserved, yet gushing. It wants to tell us everything, yet nothing at all. Voice has opinions about Miel. She has her opinions about Sam. She has opinions about that damn untilled land between their houses. She tells us all this from line one. In all her determination, she is selective; she will only be heard through the pages of this story because this Voice belongs to this setting, to these characters, to this love story.

In the pages of notes I took during Patti’s presentation and many others, I still learn the most about Voice from authors like Anna-Marie McLemore. Reading widely and hearing Voice, being able to spot her in the wild, is the best way to understand her determination. And I think Patti would agree:

“If your voice is missing, go find it. Look in Stargirl or The Fault in Our Stars. Have you read Graceling? Or Wednesday Wars? What does Kate DiCamillo do with Despereaux Tilling? Or Kathy Erskine in Mockingbird? Go find it.”–Patti Gauch